Words by Robert Neff

Images from the Robert Neff Collection

Up until the mid-1890s, Buddhist priests were banned from entering large cities, especially Seoul, and those who defied the ban paid for it with their lives. According to one early British visitor, George N. Curzon, who visited Korea in 1892, the ban originated during the Japanese invasion 300 years before (1592-1598), when the invaders crept into some of the towns in monastic disguise.

But modern accounts indicate that the rise of Neo-Confucianism in Joseon Korea was the primary cause of the stigma attached to Buddhism. Perhaps Curzon was unaware that during the Japanese invasions, several thousand Buddhist monks banded together, forming guerrilla units that wreaked havoc amongst the Japanese forces.

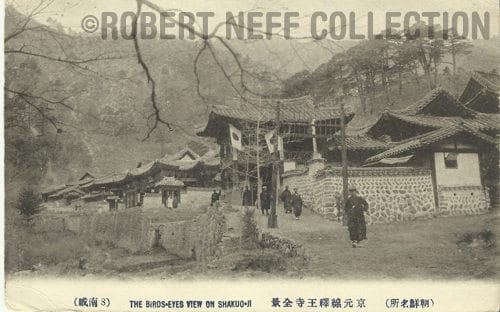

Although the monks were not allowed to enter the cities, Buddhism had a role in Joseon Korea, especially in the defense of the country. Curzon acknowledged that King Gojong “in the neighbourhood of the capital, has one or more secure mountain retreats, hither, in time of danger, he flees to the protection of a monkish garrison.”

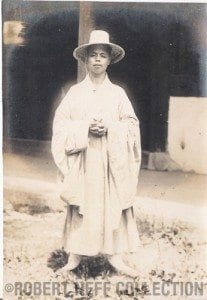

He was primarily speaking of Bukhansan (North Mountain) Fortress. Curzon did not have a good impression of the Buddhist monks whom he described as being “outcasts of society, addicted to lives of combined mendicancy, depravity and indolence.”1 He also declared that “there was not the faintest masquerade of piety among the great majority of these rather seedy scamps, some of whom were quondam criminals of the deepest dye; and this invested them with an originality which, if not admirable, was at least piquant.”

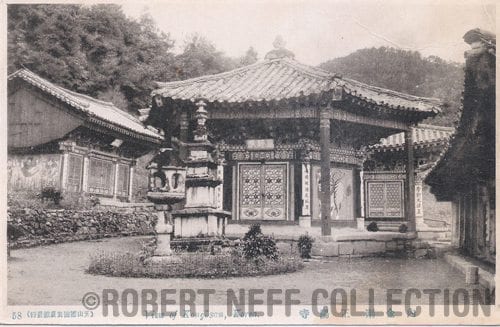

When Curzon visited the Buddhist temples of the Geumgang (Diamond) Mountains in modern North Korea, he noted that the new adepts to the temple were “with few exceptions, drawn from the ne’er-do-wells and wastrels of society, refugees from justice, the victims of official persecution, pleasure-seekers of every description, profligates and paupers, destitutes and orphans-any, in fact, who wanted a safe retreat and a quiet life. Here and there an insignificant minority preserved the traditions or kept alive the spirit of the monastic order.”

He was not the only one to have noted the contradictions of professed faith and reality. Another English visitor to the region in the mid-1890s, Isabella Bird Bishop, noted:

“There are many bright busy boys about Yu-chom Sa, most of whom had already had their heads shaved. To one who had not, Che-on, I gave a piece of chicken, but he refused it because he was a Buddhist, on which an objectionable-looking old sneak of a priest told him that it was alright to eat it so long as no one saw him, but the boy persisted in his refusal.”

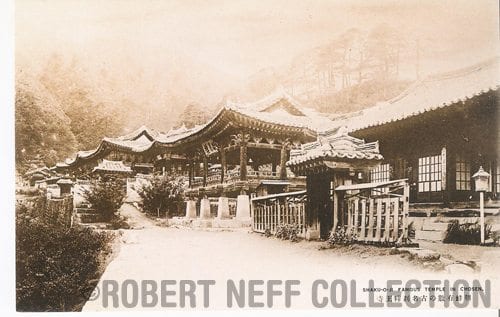

As mentioned earlier, there were Buddhist temples and monasteries on Bukhansan that played not only a role in the protection of the Joseon monarch but also as a venue for entertaining guests. Horace N. Allen wrote about his visit to the site in 1886:

“Here we found a great Buddhist temple and many surrounding buildings, one of which had been fitted up as a banquet hall for the naval guests. Here a foreign meal was served by cooks trained in foreign service (sent from the King’s palace), and washed down with the beverage brewed at Milwaukee and the sparkling “Extra Dry,” while foreign cakes, nuts and cigars, with strong black coffee, wound up the feast, which then gave place to a quaint concert by a band of performers on stringed instruments. The wild, weird strains of the music, fitting in so aptly with the untamed surroundings, made our own presence and the modern nature of the feast we had just enjoyed contrast very strangely with all about us.

[…]

After a good rest we mounted, and with an escort of the priests, who, in soldier’s garb, garrison the place, we started for the distant gate at the southern extremity of the enclosure. On our way we passed the storehouses kept constantly supplied against a time of need, while the arable land in the lower portion of the valley seemed sufficient to supply rice and vegetables enough for the occupants during a siege of indefinite length.”

In the early to mid-1890s, the Western residents of Seoul, including missionaries, escaped the oppressive heat of summer by sleeping in the Buddhist temples on Bukhansan. Despite the differences in religious beliefs, things went well except for one Samuel Moore, a Northern Presbyterian missionary who, known for his fiery passion, was not satisfied with merely maligning the opposing religion. Moore allegedly smashed some of the temple’s images. When confronted, he denied the charges and claimed:

“Not even one image was cracked or injured in the slightest degree. It was only when the chief priest of the temple had agreed with me that the images were a lot of rubbish and ought to be thrown away that I lightly tapped one as illustrating their inanity.”

Moore was somewhat notorious, at least with the American legation, for his imaginative truths. Despite the incident, some of the Buddhist priests became friends with some of the Westerners, including Clarence Greathouse (an American advisor to the Joseon government) and his elderly mother, Elizabeth. According to her diary, once the ban prohibiting priests from entering the city was lifted, she and her son were often visited by the priests who brought gifts of makgeolli, persimmons, dried seaweed and chestnuts. Clarence and his mother, apparently both alcoholics, were especially fond of the makgeolli.

Western visitors to Korea in the late 19th often had a negative impression of Buddhism. Of course, some of this was due to ignorance and religious differences. Fortunately time has made a difference and visitors flock to the temples not only to sightsee but also to stay and learn about themselves and the Buddhist faith.

1 Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, “In the Diamond Mountains: Adventures Among the Buddhist Monasteries of Eastern Korea”, National Geographic Magazine, October 1924.